Response to Parks Victoria Greater Gariwerd Draft Management Plan, November 2020

I write as a novice climber, city dweller, professional sound engineer and artist with a deep connection to nature. I have expressed my personal perspective on rock climbing in a letter to Parks Victoria, Gariwerd Wimmera Reconciliation Network and others as climbing bans expanded. The letter is available here.

The aim of this letter is to provide constructive feedback for the recent GGL DMP published by Parks Victoria in November 2020.

Rock Climbing Damage

Climbing is generating interest and popularity worldwide since it became an official Olympic sport.

R. G. Gunn, J. R. Goodes, A. Thorn, C. Carlyle and L. C. Douglas recently reported on the risks of rock climbing to rock art (Gunn et al., 2020). Gunn and colleagues explain the crucial differences between the forms of climbing but provides a questionable analogy between a mountain range and a man-made cathedral.

“Sport climbing is the act of climbing single- or multipitch routes, protected by permanently-fixed bolts and anchors drilled into the rock, using a rope and the aid of a belayer. The main difference between sport climbing and bouldering is the height of the routes being climbed and the form of protection (bouldering =no ropes, with crash pads). Likewise, traditional climbing calls for the use of temporary gear and anchors (ex. nuts, camalots etc.) to protect the climber, as opposed to permanent ones used in sport climbing (Mirsky 2016). A broader and more enlightening description is: Sport climbing offers an easier, more convenient experience which requires less equipment, less in the way of technical skills required to be safe during the climb, and lower levels of mental stress than traditional climbing. With increased accessibility to climbing walls, and gyms, more climbers now enter the sport through indoor climbing than outdoor climbing. The transition from indoor climbing to sport climbing is not difficult because the techniques and equipment used for indoor climbing are nearly sufficient for sport climbing. Whereas the transition from indoor climbing to traditional climbing is hard because traditional climbing requires significantly more in terms of techniques, experience, and equipment.” – P 87

“While Aboriginal sites are generally recorded as isolated dots across the countryside, this presents a distorted, museum-like view of Aboriginal culture. All Aboriginal sites are part of a broad cultured landscape, developed over thousands of years through maintenance, alteration and cultural associations To understand a single site, its physical, metaphysical, and cultural setting has to be assessed, Hence, while grilles and legislation may protect individual sites, the inappropriate use of the surrounding landscape, such as the cliff face between two sites, can be just as degrading to the sites themselves. For example, while avoiding the stained-glass windows, climbing on the cathedral walls that house the windows is unlikely to be tolerated as appropriate behaviour. One or two climbers might be prosecuted as larrikins, a steady stream of such thrillseekers would likely cause national outrage. It is impossible to consider the rock art of Greater Gariwerd without appreciating the physical and spiritual context of the place”- P 91

I’d like to politely challenge the – Cathedral Thrill Seekers – analogy Gunn and colleagues are making while agreeing with the notion that aboriginal sites are presented in a distorted museum like view of aboriginal culture.

Cathedrals and other culturally significant heritage buildings are often subject to intervention and modification to enable access to the public. Very carefully, with the aid of consulting heritage architects and engineers, accessibly modifications are made, amplification systems installed, electricity, modern amenities and more. Arguably, there would have been a resistance from the original builders of a heritage listed cathedral to modify their space in ways that were new and unfamiliar in the time the structure was commissioned. For example – the installation of a urinal in a heavily visited gothic era church in Europe.

I believe that in an inclusive religion, one that recognises the need of its community, there could be an imagined scenario where nature is completely off limit to mankind and manmade structures are the only one’s people are permitted to climb on. The town engineer, priest and the local climber assessing the risk, setting the route safely, making sure that the glass windows are not in any harm’s way, while educating the community about this new Olympic sport that has long human history and connections to the origin of humans in times we still had tails.

I reject the dismissal by Gunn and colleagues of rock climbers as “Thrill Seekers”. While Gunn’s work may be of great archaeological importance, I wouldn’t take his advice on any matter concerned with spirituality and religious feelings.

Bolting

The premise of the title “Rock Climbing and Rock Art – An Escalating Conflict” (Gunn etal, 2020) is confrontational in making assumptions about climbers, however, there are some sensible observations and explanations for the impact of bolting on the sandstone rock structure:

“The insertion of bolts requires a hole to be drilled into the rock to accommodate the bolt (expanding or glued). This process necessarily and permanently damages the rock and may cause premature rock decay… This process can either break down the surrounding sandstone through the expansion and contraction of the salts with fluctuating temperature and humidity (Thorn 2008) (granular disintegration) or cause horizontal fissures to widen, generating rock collapse. In the case of granular disintegration, if the regrowth of the silica skin is not rapid, the fissure expands, eventually creating a small niche (cavernous weathering). Over time this process can expand and create a new pocket or cavern within the rockshelter that relies on permanent anchors fixed to the rock for protection and contrasts with ‘traditional climbing’ where climbers must use removable protection as they climb”.

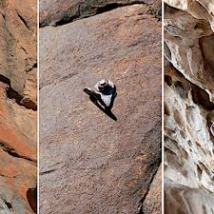

As part of GGL DMP, Parks Victoria is advancing the construction of trails and other infrastructure to support hikers and increased tourist visitation. This includes large areas of clear trail installation as illustrated in the chapter picture seen below. These structures seem to require land clearing, drilling and bolting metal directly into the rock to create hand-rails and safe observation points on fabricated decks.

How do these works align with the observations made by Gunn et al. (2020)? If there is alignment, can it be applied to the evaluation and maintenance of existing climbing routes in permitted areas?

There seems to be a conflict of interests here – Quoted from PV GGL DMP text:

‘In 2016 a native title claim was registered representing more than 1708 square kilometres of Crown land within the planning area. The claim was registered in response to the potential for native title rights in Gariwerd to be extinguished as part of the development of the Grampians Peaks Trail Project’

And further in the plan:

“Victoria’s 2020 Tourism Strategy (Victorian Government 2013) also supports enhancing the State’s nature based tourism products, such as high-quality walking experiences and associated accommodation development. The Grampians Peaks Trail will be a long-distance walking experience, showcasing the beauty and majesty of Gariwerd. Infrastructure to support the Grampians Peaks Trail and hiking opportunities across the landscape are expected to elevate the status of Gariwerd to international markets, creating a world class tourism experience that provides managed tourism to some areas while ensuring other areas remain wild”.

With the above in mind, I wonder how 1708 square kilometres of development is less damaging than a few thousand climbing bolts?

The GGL DMP seems to favour the museum like experience Gunn and colleagues identify for its touristic financial promises. It fails to consider the scale of the development proposed, while demonising fringe user groups for destroying cultural heritage.

Vs

It is interesting to note that while Gunn et al. (2020) is quoted frequently in PV decisions about climbing bans, Gunn and colleagues describe the sandstone as fragile while, in contradiction, the GGL DMP presents it as “high quality sandstone” and “really durable” which was used for construction during the colonial times.

GGL DMP page 36:

The desire for high quality sandstone for building construction in the early years of Melbourne spurred the quarrying industry, especially at Mud-dadjug (Mount Abrupt) and Gar (Mount Difficult). During the late 19th and early 20th centuries, large amounts of high-quality freestone were carved from the slopes of the Gar (Mount Difficult Range) at Heatherlie Quarry…The Heritage Council of Victoria identifies Heatherlie Quarry as of historical, scientific (technical) and social significance at the State level. The quarry provided the first really durable freestone (sandstone) discovered in Victoria

Permit System

As visitation increases, so does the need to put rules in place, and to provide additional education to all park users to raise awareness and ensure a respectful and sensible visit of the park. Signage is one way, but indeed insufficient. The GGL DMP does not clarify the climber permit system process. If an information session about access, eco system protection measures and cultural heritage protection measures was required to obtain a permit to access the park, shouldn’t this be a compulsory training for any other user group? There are many more hikers, campers and nature selfie takers than climbers who would benefit from this important education.

Singling out climbers as the only ones who need a permit to use the park sends a message that other users are free to deface the park as they please.

Graffiti

The issue around climbing chalk in Gunn and colleagues work is likened to graffiti and mentioned several times in the plan as a risk to cultural heritage. Chalk is not mandatory in climbing and can be easily banned just like the use of detergent is not allowed in wild creeks and rivers.

If graffiti is such a significant issue, there are two options and only two – police it or prevent access to all user groups. It is offensive to suggest that a fringe user group is responsible for defacing cultural heritage while other, larger and more maintenance heavy user groups with generally less environmental awareness are excused from having to apply for a permit to conduct their recreational activity.

Route Register

As part of the proposed permit system, and unique to climbers, an official Australian route register needs to be developed and PV’s willingness to discuss bolt management is a positive way forward. This information should be available to all climbers and approved by traditional owners and park authorities as part of the permit and registration process, with access notes, ecological and cultural protection measures and infrastructure maintenance schedule and details (condition / types of bolts, safety notices).

Connecting with country and Local Economy

Nowadays, nature can be experienced from the comfort of one’s home, through a glass screen, through the window of a bus and on artificial observation decks with wheelchair access on a top of a mountain. While I support sensible accessibility features and investment in sustainable facilities for tourism, I assert that the climber’s way of connecting with nature has a greater potential to make a lasting impact on any individual and thus have a greater contribution to the economy and health of a place.

As a climber, I prefer to camp in nature over staying in a hotel, I prefer to learn how navigate the landscape and feel the uneven ground over walking on a built trail, (I believe that tracks are necessary and should be clearly marked to avoid bush bashing – but tracks could be kept basic, as they generally are at the moment in the Grampians – such as the Stapylton loop walking trail) I prefer to eat locally sourced foods and connect with locals, I want to help conserve the wildlife and the park.

The average tourist might shed a few more dollars locally, but they are there for a brief moment and a selfie, possibly leaving behind a much greater quantity of destruction in the form of plastic waste (such as rubbish left behind at Mackenzie Falls). The current plan seems to be concerned about the impact of a much smaller user group, overstating their impact while understating the impact of other, much more prevalent user groups.

Threat to cultural heritage and eco systems

I reject Gunn and colleague’s assertion that the biggest threat to rock art is climbers. It is ignorance and artificial separation of people from nature. It is preferring mass popular tourism infrastructure over smaller, specialised user groups who share interest in learning and protecting the country. Education and engagement are the keys – not blanket bans subject to assessment at an undisclosed schedule.

The current plan is a reasonable but insufficient starting point for ensuring Gariwerd is managed in the best of interest of the traditional owners and preserved for future generations while providing clear information for recreational user groups.

As stated in the plan:

“Growth in community volunteering, in particular through citizen science and recreational volunteering, will continue to be vital to the landscape’s future management”

Climbers and other recreational groups are well placed to participate, and the plan should include the continuous input and expertise of specialised user groups like climbers who have gained valuable and intimate knowledge of the land over the years. Banning two thirds of the climbing while developing mass tourism is a clear statement by PV prioritising development and profit over people and country.

Appreciation and recognition of the cultural landscape

Change to naming scheme to educate and advance familiarity and connection to traditional languages by renaming of parks, reserves, mountains and geographic features with Aboriginal place names is a welcome step towards self-determination, reconciliation and inclusion.

Restoring key species

Re-introducing native species of wildlife, in consultation with ecologists which have been affected by colonialism or climate events is a welcome step towards restoring the ecosystem and respecting the country.

References

Gunn, RG; Goodes, JR; Thorn, A; Carlyle, C and Douglas, LC. Rock art and rock climbing: An escalating conflict [online]. Rock Art Research: The Journal of the Australian Rock Art Research Association (AURA), Vol. 37, No. 1, May 2020: 82-94